Organizations Have Until 2030 To Succeed In Digital Transformation

Originally published as part of, “The Day Before Digital Transformation” by Phil Perkins and Cheryl Smithhttps://www.amazon.com/Day-Before-Digital-Transformation-transformation-ebook/dp/B08LX1GYMQ

Do great leaders create the times, or do the times create great leaders? This question has been debated throughout the ages. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, three of the greatest philosophers of all time, were born within 85 years of each other and lived in the same region of Greece. Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Raphael, three of history’s most well-known artists, all painted together in a region that is now part of Italy over a period of 45 years. Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart, three of the most famous composers of all time, were born within 85 years of each other in the German Confederation. Gordon Moore (Intel), Bill Gates, and Steve Jobs, credited with revolutionizing the computer industry, were all born on the West Coast of the United States, with Gates and Jobs born in the same year.

Coincidence?

Probably not. At least when it comes to the last example on our list of greats the answer is relatively straightforward. Over the past 300 years civilization has experienced four Industrial Revolutions. Just prior to each revolution, technology components and the science behind them had evolved to a point where individuals, albeit exceptional individuals, were able to take that next step and bring the new technologies to life. The creation of a computer that was small and could be cost-effectively built for an individual to purchase and use at home was the technology leap that began the Fourth Industrial Revolution, our Digital Age. New technologies have emerged throughout our Digital Age, with some powerful ones coming to maturity now. Another set of individuals will become exceptionally wealthy and their organizations famous for figuring out how to use these emerging technologies to dramatically change the way we live and work and are entertained.

We know that now is that moment. Major changes already are disrupting organizations regardless of where you live in the world. Technology is the cause of many of the disruptions, and it is also the solution. Projections estimate that $14T will be added to the global economy by digital products and services by 2021—about 15% of global GDP and growing—up from an average of 4% to 6% annually in the prior decade.[i] The Fourth Industrial Revolution’s Digital Age changes began about 40 years ago, around 1980. History shows us that we are reaching the end of the window of opportunity to take advantage of the Digital Age technologies, and the pandemic may have closed that window even faster than the historical data predicts. We also know that there will be winners and losers.

While many scientists and researchers have studied the technological advances and impacts of the prior Industrial Revolutions, few have studied the economic patterns inherent within each revolution. Early theories were proposed by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in the 1950s, drawing the relationship between technology innovation and economic trends. He described the process of creative destruction: technology change revolutionizes economies, destroying the old one, creating a new one.[i] Christopher Freeman, an English economist, added to this view in the 1970s, focusing on the crucial role of science and technology innovation for economic development.

Carlota Perez closely collaborated with Freeman. She is currently a Professor at the London School of Economics, a British scholar specializing in technology and socio-economic development. In her 2003 book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital,[ii] Perez describes research that led to the identification of stages involved in the prior Industrial Revolutions.[iii]

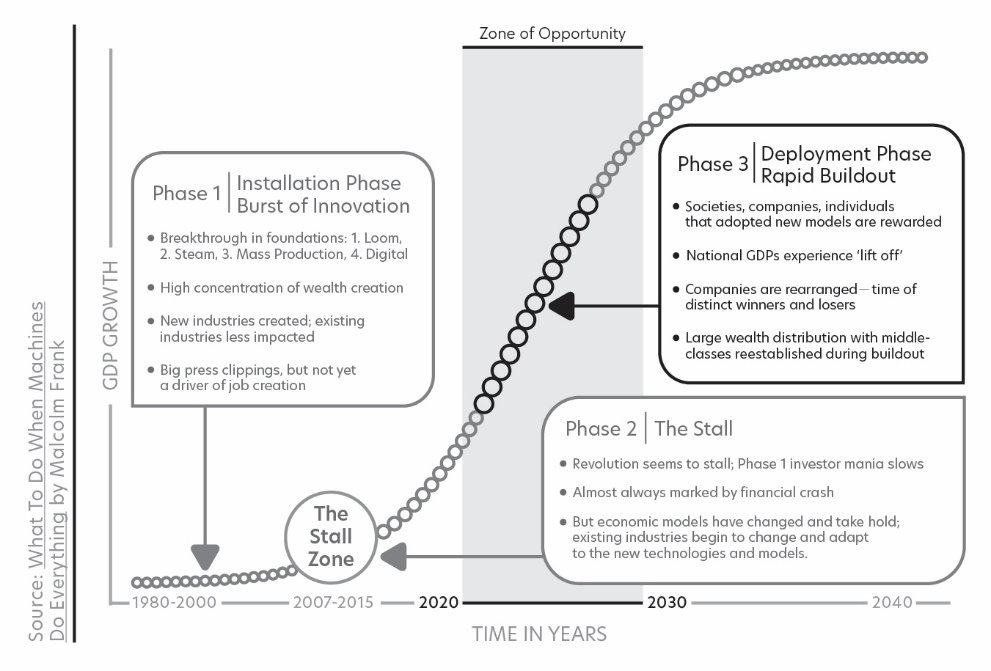

Malcolm Frank, et al., in their book What To Do When Machines Do Everything,[iv] built on Perez’ work to define the technology cycle economics from the past Industrial Revolutions and apply it to today. They identify three phases on an S-curve. (Figure 3) We use the historical patterns to identify where we are today on their S-Curve.

The first phase is the Installation Phase. This phase happens at the beginning of the age, the bottom of the S-curve, when there is a burst of innovation as new technologies come onto the market, and infrastructure begins to be built (factories of weaving machines, ocean-to-ocean tracks for railroads, assembly lines for cars, server and network infrastructures for the Internet). These are breakthroughs that destroy the old-world order, and result in a high concentration of new wealth for the initial innovators. This phase is not typically a driver of new job creation—it destroys old jobs but does not necessarily create new ones. In fact, this phase has been harrowing in terms of job loss—the Luddites attacked and burned factories that housed weaving machines in the early 1800s—and well-respected experts predicted the substitution of machinery for human labor with the invention of the steam engine would render the population redundant. John Maynard Keynes, a highly respected economist during the Third Industrial Revolution, warned that technologies that reduced the use of labor will “outrun the pace at which we can find new uses for labor.”[v] Brilliant as he was, this prediction turned out to be untrue.

This Installation Phase in the Fourth Industrial Revolution took place from around 1980 to the mid-2000s.

The Stall Phase comes next. It is almost always marked by a financial crash and recovery. The industries that are not directly affected by disruption typically do not experience financial trouble during the Install Phase. But the first phase has brought enough change, enough job loss, enough emotional upheaval in the industries that were targeted, to show everyone that the current economy is structurally changing. The disrupted sectors are starting to show weakness, while start-ups are worth fortunes. The tried and true rules of work and business no longer apply. As technology increasingly takes away jobs from the legacy firms, income inequality widens on a massive level; competition becomes fierce, organizations start globally outsourcing jobs to lower costs, and there is a steady erosion of privacy and security.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution Stall Phase happened around the mid-2000s to about 2015. Some will question whether the financial crash was a part of the Digital Age stall phase or simply the result of the subprime mortgage crisis. Ben Bernanke, the chair of the Federal Reserve during the crisis, did not blame the Great Recession (the Stall) on the housing crisis. His proof: housing values at the end of the recession were closely aligned with the values at the beginning of it. He concluded that “other pressures were at play,” and that the crisis had followed historic parallels of prior crises.[vii]

The Great Recession did follow the pattern of prior historic crises. As Malcolm, et al., point out: each industrial age before us has weathered similar storms. And according to what has happened in each of the prior ages, the stall is actually the precursor to a period of incredible technology-fueled growth as the new technologies become an intrinsic part of our lives.[viii] That happens in the next phase, and it is then that society begins to realize the great economic benefits that come with the age.

We are now at the beginning of the third and final stage in the Digital Age, the Deployment Phase. In this phase the technology innovations begin to be broadly adopted by society (the development of the western part of the US in the railroad era, the creation of suburbs, shopping malls, and fast-food chains in the automobile era). As has been experienced throughout history, the introduction of new technology does not create a dramatic rise in GDP for decades. It typically has taken 25 to 35 years for technology innovations to find their way into the established industries. But when they finally do, the economy goes into a time of rapid expansion. Organizations are created that launch new industries, and the technologies are adopted by current organizations willing and able to change within their industries. GDP growth “experiences near-vertical lift-off” (at the middle of the S-curve).[ix] For example, Great Britain rode the steam engine to massive GDP growth in the 1800s, and the United States did the same with the assembly line and electric power stations in the early 1900s. Established organizations that adopt the changes that the early and emerging technologies have ushered in will be the survivors; those that do not, usually do not make it through the middle of the Deployment Phase and rarely to the end of the age.

Over time during this third phase, when the technologies are well established and are integral to the organizations that were successful in integrating them into their product and service offerings, maturity sets in both within industries and around the globe. This is the time, at the top of the S-curve, when GDP growth stalls again. The markets stop rewarding the disruptors of that age and begin to ask, ‘what’s next?’ The beginning phase of the next revolution is already starting (sometime in the 2030s in this age), which will bring a new wave of innovations to the marketplace in the early 2040s when the cycle will begin again.

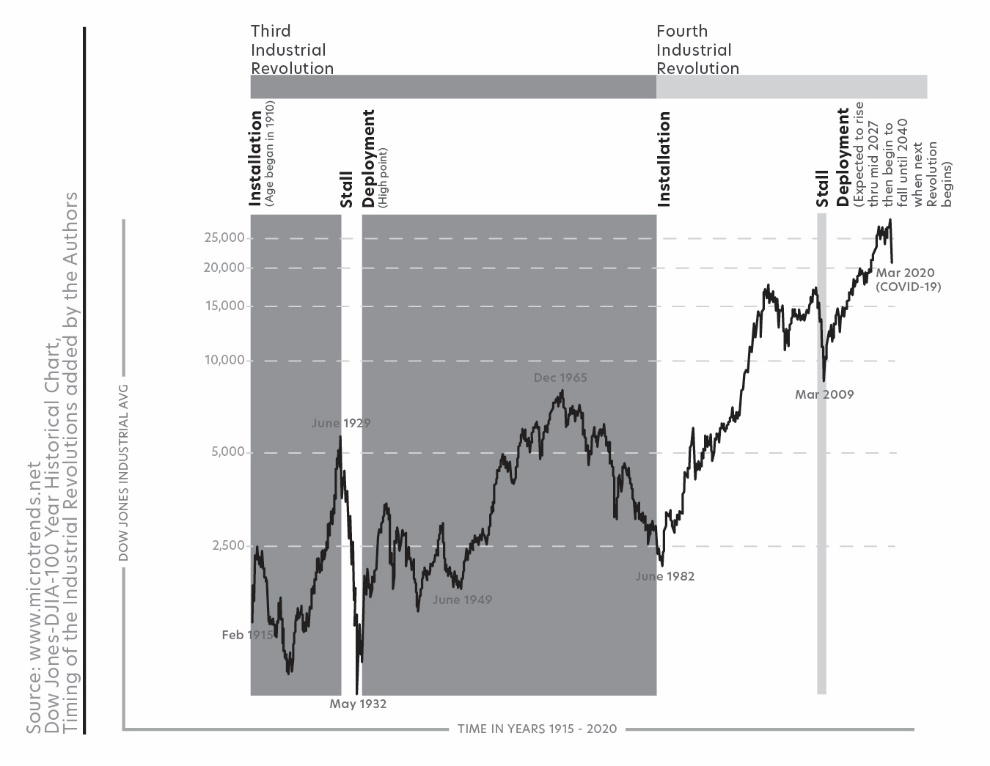

These patterns are further supported by a historical look at the stock market that mirrors the patterns we experienced in the last industrial revolution. It began with the introduction of the new technologies during which the early adopters were rewarded, was followed by a retraction, then significant market growth and expansion as they began to be universally adopted. Eventually, the markets stopped rewarding organizations for implementing the technologies because everyone had them—there were no new disruptors. The market dropped until the next technology leap took place. New technologies were invented, and the early adopters began to prove what they could do. A stall happened, but now the technologies are beginning to be generally accepted. It is uncanny the way the patterns have played out, at least between the last two ages. (Figure 4)

The early technologies of the Digital Age that established this age, such as databases, web, and mobile have matured. The inventors and early adopters have become incredibly wealthy. The Stall Phase when the investment bubble burst and the digital technologies were not yet generally accepted is behind us. The emerging technologies involved in this age that will create further disruption and provide great value to organizations that successfully adopt them have been identified and are well understood.

Time is still with us at this point in the S-curve but is running out. When we reach the mid-point of the Deployment Phase (2027-2028), there will be little left to disrupt or innovate with the technologies that have been invented during this age. The next age will be right around the corner.

Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) stock market index for the last 105 years. Historical data is inflation-adjusted using the headline CPI and

each data point represents the month-end closing value.[x]

We know the history now. We have seen the charts and the trends. Yet many of today’s leaders continue to focus on the crisis du jour by working harder to address perceived issues with their current operations. History tells us that it is time to take a new approach to address our problems.

We know that the moment to take advantage of the emerging technologies is now. The question is who will be the recipients of the immense wealth that will be created with them? The Big Tech companies took advantage of the early digital technologies in this Digital Age and continue to reap enormous value from doing so. All organizations today, Big Tech, traditional companies, not-for-profits, and governments, have an equal opportunity to take advantage of the emerging digital technologies. Who will do so correctly and creatively, and create massive value for themselves, their organizations, and for those who fund the efforts? Because there will be winners and losers.

[i] “Trends in the Information Technology sector,” Brookings Institute, Nakada Henry-Nickie, et al., March 29, 2019, 2. “…the digital economy is worth…15.5 percent of global GDP.”

The 15.5% number also quoted in Digital Economy Report 2019, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Statistics are from 2019, pre-covid19 pandemic.

[i] History of Economic Analysis, Schumpeter, J.A., London, George Allen & Unwin, 1954.

[ii] Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: the Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages, Carlota Perez, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2002.

[iii] Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, Carlota Perez, book summary.

[iv] “What To Do When Machines Do Everything, how to get ahead in a world of AI, algorithms, bots, and big data,” Malcolm Frank, Paul Roehrig, and Ben Pring, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., copyright 2017 by Cognizant Technology Solutions US Corporation.

[v] John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, quoted in Essays in Persuasion, New York, W. W. Norton & Co., 1963, 358-372.

[vi] What To Do When Machines Do Everything, Malcolm Frank, et al., 21. We have reproduced and modified this figure to add a Digital Age timeline based on our research on the past Industrial Revolution Ages.

[vii] The Courage to Act: A Memoir, Ben Bernanke, W.W. Norton & Co., 2015, Chapter 18.

[viii] What To Do When Machines Do Everything, Malcolm Frank, et al.,13-14.

[ix] What To Do When Machines Do Everything, Malcolm Frank, et al.,18.

[x] Dow Jones – DJIA – 100 Year Historical Chart, Microtrends.net. The authors added the overlay of the historic economic patterns relating to the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolutions.